Deconstructive Enquiry

Conflict done poorly is damaging.Conflict not done at all is disastrous.

Conflict done right fuels great ideas and growth.

Here's how to make the latter happen.

Adapted from the work of Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey

Why Deconstructive Enquiry matters

Few things cause more angst for both staff and leaders than the prospect of conflict, and for good reason. For most of us, our past experiences of conflict are typically a mess of heated emotions, ego clashes, and irrational arguments that deliver little progress, leaving team trust in tatters.

The only thing worse than destructive conflict is the paralysis caused by artificial harmony, where nobody rocks the boat, bad ideas persist, resentment spreads, the real issues aren't tackled, risks are ignored, and the organisation stagnates.

So what are leaders like you to do?

Standard advice it to use some form of "constructive criticism". On the surface, it makes sense; politely tell people what's wrong, offer a fix, then they'll improve. So, you're helping, right? Not so fast.

This is highly problematic for a few reasons because it assumes:

- You have the full picture. (impossible)

- There's one right answer and it's yours. (unlikely)

- It's your job to 'help' them see things 'correctly', and they're obligated to listen and accept what you say. (patronising)

- Critiquing behaviour is the best way to change behaviour. (false)

Not only is this poor logic, it triggers shame and defensiveness, especially when you have more power in the relationship.

At an organisational scale, this has a chilling effect on truth-telling and new ideas, incentivising a performative culture, where individuals seek praise and avoid blame. As people manoeuvre to maximise their own safety; distrust, secrecy, and political games infect the culture. Information integrity and collaboration breaks down, and with it, the performance of the firm.

As you can imagine, this is precisely the opposite of what modern work demands; people who can take initiative, adapt, innovate, problem-solve, and collaborate.

Deconstructive enquiry offers a path out of this bind. It enables you to harness the passion and energy of conflict to generate better ideas and decisions without it turning toxic?

It replaces rigid debate with curiosity and dialogue. Instead of stubbornly arguing your perspective as 'THE' truth, you examine the lens through which you and your colleague made meaning of the situation.

This creates a space where both people can reduce the anxiety around disagreement and start using it as a tool of discovery.

When done well:

- both parties gain a deeper understanding of how to improve the situation

- psychological safety is increased

- the conditions for truth and trust are reinforced

- relationships strengthen

- conflict transforms into an opportunity for learning, growth, and surfacing good ideas

What is Deconstructive Enquiry?

At its core, Deconstructive Enquiry appreciates that none of us can possibly have a complete picture of reality. All we have is a thin sliver that we construct based on our habitual mental models, assumptions, partial information, and interpretations.

If we accept that fact, and lean into it with humility and curiosity, we can combine our perspectives to construct a more complete understanding of the reality we face.

Through this lens, conflict ceases to be something to avoid, and instead becomes a respectable and learning-rich way to figure out what's really going on.

In practice, it's an approach to dialogue that explores how someone made sense of a situation and the internal logic that drove their decisions and behaviour.

It is neither destructive (tearing down or punishing) nor constructive (building up, instructing, coaching). Nor is it a method to persuade or control.

| Dimension |

Conventional Approach Constructive communication for informative behavioural change |

Transformational Approach Deconstructive Enquiry for organisational learning |

|---|---|---|

| The effective communicator... | Gets the person to change | Creates a context for learning |

| The primary theatre of activity... | Is external, the manager discusses the actions or inactions of the other person (the subordinate) | Is internal, both people discuss the meanings and assumptions of both parties |

| Who is at risk of learning? | Only the other person (subordinate), and even then only learning about what the communicator thinks or wants for the other | Both parties |

| How the other (subordinate) is seen? | As a misbehaver, doer of actions, a transaction | As a whole meaning maker or system whose actions or choices express some general belief, conviction, principle, theory |

| Who has the truth of the situation? | The communicator (manager) knows the truth | Neither necessarily, perhaps either, both, or neither, they do not know (yet) |

| Who doesn’t get it? | The other: "You are lost, missing something... the manager takes a teaching stance vs an enquirer’s stance" | The communicator/manager doesn’t get it... they offer a genuine report of puzzlement and inquire into how this can make sense |

| The essence of conflict... | A management problem in need of resolution | A rich resource for individual and organisational learning |

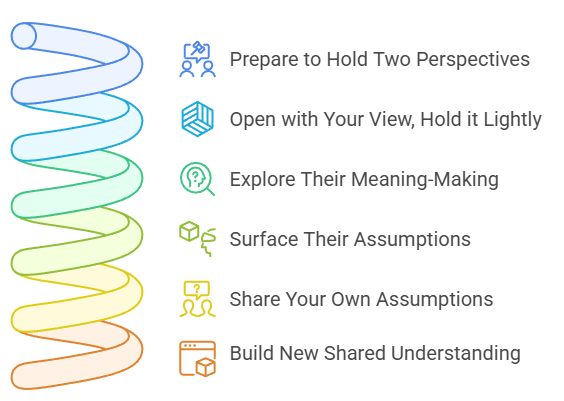

How to do it

This process is structured but not rigid. Let the conversation be organic, allowing for back-and-forth sharing in the middle stages.

Step 1. Prepare Yourself

Let go of rigid binary 'all right or all wrong' thinking. You don't have to give up your view, in fact, it's better if you don't right now. Your view has merit. Their view has merit. Neither is a complete picture of reality. That tension becomes the engine of learning.

Take a short pause before the conversation:

- Notice the judgement you are holding.

- Name it internally as “my interpretation”.

- Remind yourself that meaning is being created, not discovered.

This creates the mental space for genuine curiosity and shared meaning making.

Step 2. Open with your view

Describe the issue without claiming ownership of the truth.

- “This is how I’ve understood what happened.”

- “Here’s why it concerns me.”

- “I may have this wrong. Tell me how you saw it.”

Step 3. Explore their meaning-making

Speak from puzzlement and curiosity, not certainty.

Instead of “Here’s the issue…”, use simple, direct questions that open their thinking:

- “What led you to interpret the situation that way?”

- “What were you assuming would happen?”

- “What pressures or constraints influenced your choice?” (Questions like this are especially important because it helps reveal their hidden competing commitments. eg. wanting to: be easy to work with, hit a KPI, appear indispensable etc)

- “What information mattered most to you at the time?”

Listen deeply. Follow the thread.

Each answer reveals the next question.

Step 4. Surface assumptions

When you hear an assumption, make it explicit:

- “It sounds like you expected X. What made that seem true?”

- “What belief is underneath that choice?”

- “What risk were you trying to avoid?”

This is where transformation happens.

People see the structure behind their decisions.

Step 5. Share your own assumptions

Offer your interpretation with humility:

- “Here’s the assumption I was holding. I can see how it shaped my judgement.”

This equalises the field and lowers the defence.

Step 6. Build new understanding together, then act on it

Once both perspectives are on the table, use the contradictions to build a more complete understanding.

Note: Be careful not to rush to resolution - the pull to confirm pre-existing worldviews will be strong, and if you've got the power in the relationship, it's likely the other person will capitulate to your assessment. In that case, you'll 'feel right', but you won't be any the wiser.

Ask:

- “What do we now see that we didn’t see before?”

- “How might each of us be helping to keep this pattern in place?”

- “What assumptions still help us?”

- “What might we test or change next time?”

Closing Thoughts

The conversation should change both people.

If either person walks away with their assumptions unchallenged, it wasn't an effective deconstructive enquiry.

Deconstructive Enquiry doesn't reduce conflict, it improves it.

Conflict means something important is on the line and the people involved care about it. Consequently, if your organisation previously had an atmosphere of artificial harmony, you may find conflict increasing. Don't panic, just keep it civil.

Yes, it's slower, but it'll save you time and resources.

Over time you will find that a habit of Deconstructive enquiry means you're tackling the real sources of problems and spending less time on superficial fixes that either don't work, or lead to more rework down the line. Stick with it.